Buddha Dhamma

Preface

It has been almost 2600 years since the Buddha passed away, many changes happened in this world. Many Kings and their Kingdoms came and disappeared into dust, but the ‘Teachings of Buddha’ is still shining like the Sun on horizon. Though, due to political turmoil it was hidden for some centuries behind the clouds of confusion, and fraud and fabrications. However, as Buddha says, “Three things, cannot be hidden for long and those things are: The Sun, The Moon and The Truth.” This truth of law is equally and justly apply about his teachings. The place where the Buddha was born, got enlightenment, and shared his knowledge with the people of very land throughout of his life, the children of the same people forgot his name and his teachings. Those whose forefathers and forefathers of many generations had been supporters and followers of Buddha, they have become enemies of him. Not only they have forgot him, but they revile, defame, discredit, misinterpret and abuse out of ignorance to him who was the unparallel teacher for the entire mankind. In the extremity of madness, they do not recognise their real father, instead of it they have embraced the imaginary fathers and mothers who have been never existed. Neither they have done any good for their forefathers since 1000 B.C. nor doing anything good for themselves in current period. However out of madness they embracing them only to increase their sufferings. Wherever excavation happened, only Buddhist heritage comes out from under the surface of earth which has been buried by some traitors with the help of foreign invaders.

Under British Rule, Year 1837, James Princes was successful in reading of Asoka’s Rock Inscriptions which is written in Dhamma Lipi. Since then, actual History of India started coming out before the world. As soon as this matter came into light to the world, many traitors started writing fake books to misguide the masses to prevent them to know the actual History and culture of India. It has been almost two hundred years passed since partial truth of Indian history has been revealed. Many fake characters have been created to misrepresent the actual history. The question arises, “How to find the actual history?” There are two ways to find the actual history. One is through archaeological evidences and Other is by understanding the language which was prevailed in Indian society till its culture was intact i.e by scientific study of archaeology evidences and Pali languages and its script. Buddha is considered the foundation of rationality in Jambudeepa. He himself given a sermon, “Don’t believe in anything that is written in books, Don’t, go by saying, Don’t, go by tradition… unless it agrees to common senses and facts.”

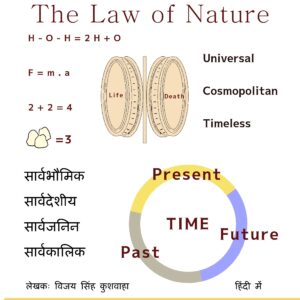

There are many books available in market written on Buddhism. Almost all are contradicting and misleading to one another. People are confused, “What is the truth and how to reach the truth?” Tripitaka is considered the collection of Buddha’s teachings and some learned monks. But it cannot be said whatever is currently available in Tripitika is cent per cent true teachings of Buddha’s. The first reason is- It was compiled many centuries later since Buddha passing away. The actual compilation of Tripitika is unknown. Original manuscript of it, is not available at this time. Why it was not composed at the time of Buddha? There were many reasons of it. At the time of Buddha, writing of such numbers of suttas was not easy task because paper was not invented by that time. Even Kings used only very important order to write on clothes to deliver the recipient and by using seal. Moreover, Buddha wanted people to actual practice the Dhamma rather than putting into books. Dhamma has no meaning and useless unless it come into practice. This is the first reason that it was not compiled. It was carried forward for many centuries Orally by mentor-disciple tradition. Many thing changes with time like language and the way of living of people. Everyday new challenges come and so is its solutions. However, there are certain things which never changes e.g., Law of nature. Buddha’s teaching is discovery of nature and it laws. As the ‘Law of Nature’ can be verified at any time by anybody, so is the teachings of Buddha. The Buddha says, “The whole world is continuous flux. It is impermanent. Everything changes with time therefore develop your wisdom”. In search of truth, I read more than 100 books written on Buddhism. It was very difficult to reach to the truth like other people. Recently, I got a chance to read writings of Rajiv Patel Books: Vaidik Yug Ka Ghalmel and Bhram Ka Pulinda and Buddhjiviyon Ka Sadyantra. These books are amazing and eye opening. Another Linguistic expert and writer is Dr. Rajendra Prasad Singh. His books: Baud Sabhyata Ki Khoj, and Itihas Ka Muyanna, Bhasa, Sahitya Aur Itihas Ka Punarpath are equally importance. After reading these books many things became clear and almost able to reach the truth. By learning Pali language and its transformation and development, India’s History could be well understood. Without Pali Language and its Script ‘Dhamma Lipi’, neither ‘Buddhist Philosophy’ nor India’s History could be well understood.

Human society need some cultures and traditions to live. Without it, life is lack of hope, encouragement, peace and happiness. There must be something to bring people together to exchange their ideas, feelings and emotions. Festivals and traditions are best way to keep well knitted in social tread because human being is social animal. If culture and tradition based on equality, morality, justice and brotherhood and truth, people lives will be happy and they will live in peace and country will prosper. On contrary, masses will suffer and few will enjoy.

The Teachings of Buddha based on truth, based on equality, morality, social justice and brotherhood. There is place of God, and soul which is most dangerous things for humanity and culturing of mind. These two things are root of all evils. It gives upper hand of some people to exploit the masses.

Present Books ‘Buddha Dhamma’ is said to be the new version of the book titled ‘The Buddha and His Dhamma’ written by Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. I have modified and omitted few lines which were not matching with evidences and logic. Dr. Ambedkar has done great work of his time. There were many things which were unknow at his time. New discoveries and researches entail us to write this book to emove confusion from the mind of people. Dr. Ambedkar himself filtered out many impurities and appendix from books available on this Philosophy at his time. Now, we should follow his foot- steps to further filter out some impurities from the doctrine. This is necessary because our cultures and philosophy was completely destroyed and eradicated from this land. If further generation find still find something ‘wrong and impure’ they can filter out. This is way to keep this tradition pure and continuous for the benefit of own and for the whole world. Because buddha teaching is the rarest of rare to find. It is the excellent in beginning, Excellent in middle and Excellent in end. That is why ‘Buddhist Dhamma Council’ used to be held from time to time to filtered out any impurities, and inconsistency which comes in due course of time. I hope this book will help people to reach to the truth and open a door of Happiness in their lives.

Thanking you.

Author and Editor: Vijay Singh Kushwaha

INDEX

BOOK ONE

SUKITI GOTAMA- HOW HE BECAME THE BUDDHA

Part I— From Birth to Parivajja

Part II— Renunciation for Ever

Part III— In Search of New Light

Part IV— Enlightenment and the Vision of a New Way

Part V— The Buddha and His Predecessors

Part VI— The Buddha and His Contemporaries

Part VII— Comparison and Contrast

BOOK TWO

CAMPAIGN OF CONVERSION

Part I — Buddha and His Vishad Yoga

Part II — The Conversion of the Parivajjakas

Part III — Conversion of the High and the Holy

Part IV — Call from Home

Part V — Campaign for Conversion Resumed

Part VI — Conversion of the Low and the Lowly

Part VII — Conversion of Women

Part VIII —Conversion of the Fallen and the Criminals

BOOK THREE

WHAT THE BUDDHA TAUGHT

Part I — His Place in His Dhamma

Part II — Different Views of the Buddha’s Dhamma

Part III — What is Dhamma

Part IV — What is Not Dhamma

Part V — What is Saddhamma

BOOK FOUR

RELIGION AND DHAMMA

Part I — Religion and Dhamma

Part II— How Similarities in Terminology Conceal Fundamental Difference

Part III — The Buddhist Way of Life

Part IV — His Sermons

BOOK FIVE

THE SANGH

Part I — The Sangh 7

Part II — The Bhikkhu:The Buddha’s Conception of Him

Part III — The Duties of the Bhikkhu

Part IV — The Bhikkhu and the Laity

Part V — Vinaya for the Laity

BOOK SIX

HE AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES

Part I — His Benefactors

Part II — His Enemies

Part III — Critics of His Doctrines

Part IV — Friends and Admirers

BOOK SEVEN

THE WANDERER’S LAST JOURNEY

Part I — The Meeting of those Near and Dear

Part II — Leaving Vaishali

Part III — His End

BOOK EIGHT

THE MAN WHO WAS SUKITI GOTAMA

Part I — His Personality

Part II — His Humanity

Part III — His Likes and Dislikes 8

BOOK ONE

SUKITI GOTAMA — HOW HE BECAME THE BUDDHA

Part I : From Birth to Parivajja

Part II : Renunciation for Ever

Part III : In Search of New Light

Part IV : Enlightenment and the Vision of a New Way

Part V : The Buddha and His Predecessors

Part VI : The Buddha and His Contemporaries

Part VII : Comparison and Contrast 9

PART I

FROM BIRTH TO PARIVAJJA

- His Clan

- Ancestry

- Birth of Prince

- Asita’s Visit

- Death of Rummin

- Childhood and Education

- Early Traits

- Marriage

- Father’s Plans

- Admonition to the Prince

- The Prince’s Reply to Udayin

- Birth of Rahula

- Initiation into the Sakya Sangh

- Conflict with the Sangh

- Parting Words

- The Prince and the Servant

- The Return of Channa

- The Family in Mourning

Kingdom of Sakyas

Time: 6B.C.

1.His Clan

Sixth century B.C., India was not a single Sovereign country. At that time, it was known as Jambudeepa. The Whole continent was divided into many States. Some of them were large, some were small. Among these some were monarchical and some non-monarchical. In North Jambudeepa, the monarchical States were sixteen in total. Their names were Anga, Magadha, Kasi, Kosala, Vajji, Malla, Chedi, Vatsa, Kuru, Panchala, Matsya, Saursena, Asmaka, Avanti, Gandhara and Kambhoja.

The non-monarchical States were eight in numbers. Those were of the Sakyas of Kapilvatsu, the Mallas of Pava and Kushinara, the Lichhavis of Vaisali, the Videhas of Mithila, the Koliyas of Ramagam, the Bulis of Allakapa, the Kalingas of Resaputta, the Mauriyas of Pipphalvana and the Bhaggas with their capital on Sumsumara Hill.

The monarchical States were known as Janapada. The larger monarchical States were Kosala and Magadha. These were known as Mahajanapada. Monarch of Kosala Kingdom was Pasenadi and of Magadha was Bimbisara. The non-monarchical were known as Sangh or Gana. Republic of Sakyas was located in northern part of India. The capital of its state was the city called Kapilavathhu. It was ruled by Sakyas. it was republican state however, its sovereignty was attached with Kosala Monarch. Due to this, the king cannot exercise some power. There were many ruling families of Sakyas Republic. They used to rule in turns. Throned ruler was known as Raja or King.

2.Ancestry

Family tree of Sakya as per known records was as: The first king of Sakya dynasty who established Kapilavatthu as a capital was Jayasena. He had had a son. His name was Sihahanu. Sihahanu was married to Kaccana. Sihahanu had five sons. Their names were- Suddhodana, Dhotodana, Sakkodana, Suklodana and Amitodana. Besides this,

Sihahanu had two daughters. Theirs name were Amita and Pamita. Suddhodana was married to Rummin (Mahamaya name first time appeared in ‘Buddha Charitam’ of 2nd Century AD). Rummin’s father’s name was Anjana and her mother’s Sulakhana. Anjana was from a Koliya tribes. Sakya and Koliya were two prominent tribes of ruling class of north India. Rummin was resident of village called Devadaha. It was 90 km in east to Kapivatthu.

Suddhodana was skilled in a great military prowess. At that time, a king could have multiple wives. To have second wives, the king had had to prove his martial art at arena. Suddhodhana proved it. He was allowed to have second wives. He chose Mahapajjapati Gotami as a second wife. She was elder sister of Rummin.

Suddhodana was the king of Sakya Republic. He held a large scale of land. There were many retinues in his service. Being a king, he was very rich man. He held land at such large extent that he employed one thousand ploughs to till it. He savoured quite a luxurious life. He had had many palaces to live in. He had had many personal pleasure gardens for amusement.

3.Birth of Prince

There was a custom among the Sakyas to observe an annual midsummer festival. It used to be grand festival which fell in the month of Asad. The celebration of festival would last for seven days. It was celebrated by all the Sakyas throughout the State and also by the members of the ruling family. The queen Rummin was to have first bay. She was pregnant. There was an old custom in north Jumbudeepa where a daughter would to go to her parent home for delivery of her first baby. Since, Rummin was to bear her first baby, so she decided go her parents’ home. She also wanted to observe the festival with gaiety, with splendour, with flowers, with perfume.

One night, the queen bathed herself in lotus pond and went to sleep. There a story goes-

After bath, the queen went into her royal chamber for sleep. She soon fell asleep. While she was asleep, she had

a dream. In her dreams, she saw that the four world-guardians kings raised her as she was sleeping on her bed and carried her to the tableland of the Himalayas. They placed her under a great ‘sal’ tree and stood on one side. The wives of the four world-guardians kings then approached and took her to the lake Mansarovar. They bathed her and robed her in a heavenly dainty dress. They anointed her with perfumes and decked her with flowers. Then a white Elephant carrying holding lotus flower in his trunk approached to her. The elephant changed into lotus flower and disappeared into her belly. At that moment the queen awoke. Next morning, the queen shared her dream to the King Suddhodana. Not knowing how to interpret the dream, Suddhodana summoned eight Samanas who were most famous in spiritual knowledge. Their names were Rama, Dhaga, Lakkana, Manti, Yanna, Suyama, Subhoga and Sudatta. Samanas were great revered people. The king caused the ground to be strewn with welcoming flowers and high seats were prepared for them. He got prepared excellent food for them to eat. When they came, he himself received in person. They were served food and after having food the king put the dream of her queen before them to interpret. All Samanas listened the dream carefully and come to conclusion that queen was going to born an extra ordinary baby. Hearing this, the king and queen overjoyed with bright prospects.

The queen desired to go to her parents’ home for delivery. The king approved her wish. The queen seated in her in a golden palanquin borne by four couriers. The king sent her forth with a great retinue to her father’s house. Rummin, on her way to Devadaha, had to pass through a pleasure garden of sal trees and other trees, flowering and non-flowering. It was known as the Lumbini Grove. As the palanquin was passing through it, the whole Lumbini Grove seemed like a ‘heavenly grove’. The tips of the branches of the trees were loaded with fruits, flowers. Bees were humming, uttering curious sounds. The flocks of various kinds of birds, singing sweet melodies. Witnessing scene of grove was so spender that there arose a desire in the heart

of Rummin for halting and sporting therein for a while. She asked the couriers to take her in the sal-grove and wait there. The procession went into Lumbini Garden. Rummin, the queen alighted from her palanquin. She walked up to the foot of a royal sal tree. A pleasant wind was blowing. The boughs of the trees were heaving up and down as if they were welcoming the queen. The queen, felt like catching one of them. Luckily one of the boughs heaved down sufficiently low to enable her to catch it. She rose on her toes and caught the bough. Immediately, she was lifted up by its upward movement and being shaken. She felt the pangs of childbirth. The midwives were also present her. She asked them to help her to bed. The nurses, immediately helped her to free her hands from the branch. They prepared suitable bed of delivery there. She born a beautiful baby son. Its’ date was Vesakh Punnima, Year 563 B.C. Since, child was born before reaching to queen’s father house, there was no use of going to her father home. Immediately, two couriers were sent, one to Kapilvatthu and other to Devadaha her father home of this news. Suddhodana and Rummin were married for a long time. But they had no issue. Ultimately when a son was born to them. The birth of baby prince was celebrated with great rejoicing. There was held a great pomp and ceremony by Suddhodana and his family and also by the Sakyas.

4.Asita’s Visit

There dwelt on the Himalayas a great Samana named Asita. Asita heard the news of newly born Prince. It was custom and great honour to have blessing of wise and great Samans on such occasion. The king himself sent invitation to Great Samana Asita for his blessing.

Asita was living with his nephew Narada along with other disciples. He took his nephew along with him and left for the palace. The king Suddhodana was engaged in welcoming and celebration and ceremony of his family and friends in the palace. There were door keepers standing at the gate. The sage, Asita arrived at palace and saw through gate of palace that many hundred or thousand beings had

assembled. He asked the door-keeper to inform the king of his arrival. The king himself came to welcome him. The king got prepared seats for Asita and his nephew. Then Suddhodana bowed in reverence to Asita and offered him the seat. After seeing him seated in comfort, The king asked the well beings and health of the sage. At that time, the baby prince was asleep. The king asked the sage to wait for some times to see the baby. A great desired rose in sage heart to see the baby prince as soon as possible as if he was holding some great expectation from child. He wished to the king to see the child even in sleep. Seeing the great desired of sage, the King could not resist and went to chamber of baby prince. He himself held baby in hand and approached to sage. By that time, the prince was awaked. Asita observing the child very carefully, beheld that the prince was endowed with the extra ordinary marks of a great man. His shape and beauty were surpassing to a common mortal prince. Here a story goes-

The sage was mesmerized at the features of baby prince and brusted into solemn utterance, “Marvellous, verily, is this person that has appeared in the world,” and rising from his seat clasped his hands, fell at his feet, made a right-wise circuit round and taking the child in his own hand stood in contemplation. Asita somehow came to conclusion that this child was going to achieve some extra ordinary achievements. He was in speaking in great admiration of praise and honour. After some times, he looked the child again and again and all of sudden, he brusted into weeping. He wept and shedding tears, sighed deeply. Suddhodana beheld Asita shedding tears, and sighing deeply. Beholding him thus weeping, the king got alarmed and in distress asked to Asita, “Why, O Sage, do you weep and shed tears, and sigh so deeply? Surely, there is no misfortune in stored for the child.” At this, Asita said to the king, “O King, I weep not for the sake of the child. There will be no misfortune for him. But I weep for myself. I am old, aged, advanced in years, and this boy will without doubt become a great enlightened person. And having done so, will turn the supreme wheel of the doctrine that has not been

turned before him by any other being. He will do it for the out of compassion for the weal and happiness of the world, and he will teach his doctrine. The supreme ‘Doctrine of Life’ that he will proclaim, will be good in the beginning, good in the middle, good in the end. It will be complete in the letter and the spirit, whole and pure. The enlightened being Buddhas are very rare to appear in the world. So also, O King! this boy will without doubt obtain supreme, complete enlightenment, and having done so will take countless beings across the ocean of sorrow and misery to a state of happiness. I am advanced in age and old. I shall not be alive to see his achievements. Therefore, 0 King, I weep and in sadness. I sigh deeply, for I shall not be able to reverence him.” The king got relieve from such unpleasing state of confusion.

The king thereafter offered to the great sage Asita and Nardatta, his nephew, suitable food, and having given him robes made a right-wise circuit round him. Thereuponn Asita said to Nardatta, his nephew, “When you shall hear, Nardatta, that the child has become a Buddha, then go and take refuge in his teachings. This shall be for thy weal and welfare and happiness.” So saying Asita took leave of the Raja and departed for his hermitage.

5.Death of Rummin

As per the family tradition, the name ceremony was held on the fifth day from birth. At palace, ‘Name Ceremony’ took place. The name chosen for the child was Sukiti. As per many books, his childhood name was said to be Siddhartha or Siddhatha, but Siddhartha or Siddhatha name first time appeared in 2nd century(80AD-150AD) in a book ‘Buddha Charitam’ written by Ahwaghosa in Hybrid Sanskrit. Sanskrit was not yet completely developed. It was in nascent phase of Development. At the time of Buddha, Pali was the spoken language of masses and officials. The script which was used for writing was Dhamma Script. Siddhartha name could be not written in Dhamma Lipi. Moreover, not a single Asoka’s inscription bears name Siddhartha. All inscriptions bear name Sakya Muni Buddha. Many other titles have also been

dedicated to him representing his virtues like: Sugat, Tathagata, Samyak Sambuddha etc. The burial’s articles received from Piparahava’s site, bears his name Sukiti. His clan’s name was Gotama. Popularly, therefore, he came to be called Sukiti Gotama. In the midst of rejoicing over the birth and the naming of the child, queen Rummin suddenly fell ill and her illness soon became very serious. Realising that her end was near she called King and her sister Pajapati bedside her and said, “I am sure that the prophecy made by Asita about my son will come true. My regret is that I will not live to see it fulfilled. My child will soon be a motherless child. But I am not worried in the least as to whether after me my child will be carefully nursed, properly looked after and brought up in a manner befitting his future. I entrust my child to you, my sister. I have no doubt that you will be to him more than his mother. I am relieved and happy of having such a sister as queen. Permit me to die. The time of departure has come. The death is waiting to take me.” So saying, She breathed her last and died. Both Suddhodana and Pajapati were greatly grieved and wept bitterly. The prince was only seven days old when his mother died.

In due course of time, Pajapati Gotami bore her child. He was named Nanda. Besides this, he had also several cousins. Mahanama and Anuruddha, sons of his uncle Suklodan, Ananda, son of his uncle Amitodan, and Devadatta, son of his aunt Amita. Mahanama was older than Sukiti and Ananda was younger. Sukiti grew up in their company.

6.Childhood and Education

When prince Sukiti was able to walk and speak; all the Sakyas liked him very much. He became dear eye to them. Everybody wanted to play with him. At the age of eight his education started. He was provided the best teachers to teach him. The child prince was very attentive in learning. He soon learned all what they taught. After basic education, the king Suddhodana sent for Sabbamitta of distinguished teacher as a philologist and grammarian. As per custom, Suddhodana handed over the prince to his charge, to be taught. He was his second teacher. Under him, Gotama

mastered all the philosophic systems prevalent in his day. Besides this, he learned the science of concentration and meditation. He was also provided the best military training as befitting for a prince.

7.Early Traits

Whenever the prince got free time, he repaired to a quiet place, and practised meditation. The prince Sukiti was of kindly disposition. He did not like exploitation of man by man. Once he went to his father’s farm with some of his friends. he saw how the labourers ploughing the land, raising bunds, cutting trees, etc. All were dressed in scanty clothes and working under hot glaze of burning sun. He was greatly moved by the sight. He asked to his friends, “can it be right that one man should exploit another? How can it be right that the labourer should toil and the master should enjoy the lavish live on the fruits of his labour?” His friends did not know what to say. For all they got learned that the laborers were born to serve their masters. he was only fulfilling his destiny.

The Sakyas used to celebrate a festival called Vappamangal. It was a rustic festival performed on the day of sowing. On this day, custom had made it obligatory to every Sakya of right age to do ploughing personally. Sukiti the prince always observed the custom and did engage himself in ploughing every year. Though he was a prince and a man of learning, he did not despise manual labour. He had been taught archery and the use of many kinds of war weapons. But he did not like causing unnecessary injury. While his friends liked hunting, he refused for sports hunting. If his friends encouraged him, “Even it is not for hunting, come to witness how accurate is the aim of your friends,”. Even such invitations he refused by saying, “I do not like to see the killing of innocent animals.”

Pajapati Gotami, the foster mother of prince, was deeply worried over the attitude of Sukiti. She used to argue with him saying, “You have forgotten that you are a Khattiya and fighting is your duty. The art of fighting can be learned only through hunting. Hunting gives you opportunities to 18

verify and sharpen your aiming skills accurately. Hunting is a training ground for the warrior class.” To this, prince often used to ask Gotami, “But, mother, why should a Khattiya fight?” Qeen Gotami used to reply, “Because it is his duty to fight to protect his property and subjects.” The prince was never satisfied by her answer. He used to ask Gotami, “Tell me mother, how can it be the duty of man to kill man?” Gotami argued, “Such an attitude is befitting for an ascetic not Khattiyas. Khattiya must fight. If they don’t do so, who will protect the kingdom? “But mother, If, all the Khattiyas loved one another, would they not be able to protect their kingdom without killing?” To this, Gotami had to leave him to his own opinion.

The prince Sukiti loved meditation very much. His father suddhodhana and his mother Gotami did not like such disposition for meditation. They thought it was so contrary to the life of a noble class Khattiya. The prince believed that meditation on right subjects led to development of the spirit of universal love. He justified himself by saying, “When we think of living things, we begin with distinction and discrimination. We separate friends from enemies, we separate animals we rear from human beings. We love friends and domesticated animals and we hate enemies and wild animals. This dividing line we must overcome and this we can do when we in our contemplation rise above the limitations of practical life.” Such was his reasoning.

His childhood was marked by the presence of supreme sense of compassion. Once, he was resting under a tree of royal garden and enjoying the peace and beauty of nature. While so seated, a big bird fell from the sky just in front of him. It was a white swan. The bird had been shot at by an arrow which had pierced its body and was fluttering in great agony. Sukiti rushed to the help of the bird. He removed the arrow. He dressed its wound and gave water to drink. He picked up the bird and wrapped up it in his upper garment and held it next to his chest to give it warmth. He was wondering who could have shot this innocent bird. Before long there came his cousin Devadatta armed with all the implements of shooting. He said that he had shot a bird 19

flying in the sky, the bird was wounded but it flew some distance and fell somewhere there, and asked him if he had seen it. Sukiti replied in the affirmative and showed him the bird. At warmth of love and compassion, the bird felt ease. Devadatta demanded that the bird should be handed over to him. At this, Sukiti refused to do. A sharp argument ensued between the twos. Devadatta argued that he was the owner of the bird because by the rules of the game, he who kills a game becomes the owner of the game. Prince Sukiti objected the validity of the rule. He argued that it is only he who protects that has the right to claim ownership. How can killer could be the owner? The argument went for a long time. Neither was ready to yield. They approached for arbitration. The king was seated in court along with ministers and officials. The matter was put before them. The arbitrator upheld the point of view of Sukiti Gotama. Since then, Devadatta became his permanent enemy.

8.Marriage

There was a Sakya by name Dandapani. Yasodhara was his daughter. She was well known for her beauty and for her sila. Yasodhara had reached her sixteenth year and Dandapani was thinking about her marriage. According to custom of Khattiya, Dandapani sent invitations to suitable young men of all the neighbouring countries for the choosing of right groom for his daughter. An invitation was also sent to Sukiti Gotama. He was of same age as Yasodhara. His parents also were equally anxious to get him married. They asked him to go and offer his hand to Yasodhara. He agreed to follow his parents’ wishes. At wooing hall, amongst the young men Yasodhara’s choice fell on Gotama. Since prince was very kind in disposition and behavers, Dandapani was not very happy. He felt doubtful about the success of the marriage. He knew that prince preferred loneliness. How could he be a successful householder? Yasodhara was determined to marry none but Sukiti. Knowing her daughter’s determination to marry no one but Sukiti Gotama, the mother of Yasodhara told Dandapani that he must consent. The rivals of Gotama were not only 20

disappointed but felt that they were insulted. They wanted that in fairness to them Yasodhara should have applied some test for her selection, but she did not. For the time being they kept quiet, believing that Dandapani would not allow Yasodhara to choose Sukiti Gotama so that their purpose would be served. They demanded that a test of martial art be prescribed. Dandapani had to agree. At first prince was not prepared was not ready. But Channa, his charioteer, pointed out to him what disgrace his refusal would bring upon his father, upon his family and upon Yasodhara. Sukiti Gotama was greatly impressed by this argument and agreed to take part in the contest. The contest began. Each candidate showed his skills in turn. Gotama’s turn came and he showed the highest marksmanship. Thereafter, the marriage took place with grand show. Both Suddhodana and Dandapani were happy, so were Yasodhara and Mahapajapati.

9.Father’s Plans

After marriage, Suddhodana was relieved and ensured that his son would enjoy the married life. He thought of getting him engrossed in the pleasures and carnal joys of life. With this object in view, he got built three luxurious palaces for his son to live in, one for summer, one for the rainy season and one for winter. These palaces were well furnished with all the requirements and excitements for a full amorous life. Each palace was surrounded by a beautiful garden with all kinds of trees and flowers. The king appointed his consultant and priest Udayin, thought of providing a harem for the prince with very beautiful inmates. Suddhodana then told Udayin to advise the girls how to go about the business of winning over the prince. Having collected the inmates of the harem, Udayin first advised them how they should win over the prince. This being so, boldly put forth your efforts that the posterity of the king’s family may not be turned away from him. Thus, these young women assailed the prince with all kinds enamours of stratagems. But the prince, having his sense guarded by self-control; neither rejoiced nor smiled. Having seen them 21

in their real condition, the prince pondered with an undisturbed and steadfast mind.

10.Admonition to the Prince

Udayin the consultant and friend of prince was reported by chief of harem that the girls had failed to wind over prince. The prince had shown no interest in them. Udayin was well skilled in the rules of policy, thought of talking to the prince. He Met to the prince all alone, said, “Since I was appointed by the king as a fitting friend for you, therefore, I wish to speak to you in the friendliness of my heart. He began saying, “To hinder from what is disadvantageous, to urge to do what is advantageous and not to forsake in misfortune, these are the three marks of a friend. If I, after having promised my friendship, were not to heed when you turned away from the great end of man, there would be no friendship in me. It is right to woo a woman even by guile, this is useful both for getting rid of shame and for one’s own enjoyment. Reverential behaviour and compliance with her wishes are what bind a woman’s heart; good qualities truly are a cause of love, and women love respect. Even if your heart is unwilling, will you not have courtesy to please them with worthy of this beauty of yours? Courtesy is the balm of women. Courtesy is the best ornament. Beauty without courtesy is like a grove without flowers. But of what use is courtesy by itself? Let it be assisted by the heart’s feelings. Surely, when worldly objects so hard to attain are in the grasp, thou should not despise them.

11.THE PRINCE’S REPLY TO UDAYIN

Having heard the friendly words of minister and consultant, the prince made reply, in a voice like the thundering of a cloud, “This speech manifesting affection is well-befitting in you, but I will convince you where you wrongly judged me. I do not despise worldly objects. I know that all mankind is bound up therein. But remembering that the world is transitory, my mind cannot find pleasure in them. Yet even though this beauty of women were to remain 22

perpetual, still delight in the pleasures of desires would not be worthy of the wise man. If a great man having become victim to desires, destruction would be his lot. Real greatness is not to be found where there is destruction or a want of self-control. And when you say, ‘Let one deal with women by guile,’ I know about guile, even if it be accompanied with courtesy. That compliance too with a woman’s wishes pleases me not, if truthfulness be not there. If there be not a union with one’s whole heart and nature, I would say, overpowered by passion, believing in falsehood, carried away by attachment and blind to the faults of its objects, what is there in it worth being deceived? And if the victims of passion do deceive one another, are not men unfit for women to look at and women for men? Since, these things are so, surely as a true friend of mine, you would not lead me astray into ignoble pleasures.

Udayin felt silenced by the firm true words and strong resolve of the prince. He reported the matter to his father.

12.BIRTH OF RAHULA

Sukati and Yasodhara loved and cared very much to each other. After a long term of married life, Yasodhara gave birth to a beautiful son. He was named Rahula.

13.INITIATION INTO THE SAKYA SANGH

The Sakyas had their Sangh. Every Sakya youth above twenty had to be initiated into the Sangh and be a member of the Sangh. When Prince Sukiti Gotama had reached the age of twenty, it was time for him to be initiated into the Sangh and become a member thereof. The Sakyas had a meeting-house which they called Santhagar. It was situated in Kapilavatthu. The session of the Sangh was also held in the Santhagar. With the object of getting Sukiti initiated into the Sangh, Suddhodana asked the Purohit of the Sakyas to convene a meeting of the Sangh. Accordingly, the Sangh met at Kapilavathhu in the Santhagar of the Sakyas. At the meeting of the Sangh, the Purohit proposed that Sukiti be enrolled as a member of the Sangh. The Senapati of the Sakyas then rose in his seat and addressed 23

the Sangh as follows, “Sukiti Gotama, born in the family of Suddhodana of the Sakya clan, desires to be a member of the Sangh. He is twenty years of age and is in every way fit to be a member of the Sangh. I, therefore, move a proposal of request that he be made a member of the Sakya Sangh. Pray, those who are against the motion speak.” No one spoke against it. He repeated the second time. But, no one rose to speak against the motion. The Senapati rose and repeated the same words and said, “I ask, those who are against the motion can raise object and speak.” Even for the third time no one spoke against it. It was the rule of procedure among the Sakyas that there could be no debate without a motion and no motion could be declared carried unless it was passed three times. The motion of the Senapati having been carried three times without opposition, Sukiti was declared to have been duly admitted as a member of the Sakya Sangh. Thereafter the Purohit of the Sakyas stood up and asked Sukiti to rise in his place. Addressing Sukiti, he said, “Do you realize that the Sangh has honoured you by making you a member of it?”

Sukiti: I do, sir.

Purohit: Do you know the obligation of membership of the Sangh?

Sukiti: I am sorry, sir. I do not know, but I shall be happy to know them.

Purohit: I shall first tell you what your duties as a member of the Sangh are:

(1) You must safeguard the interests of the Sakyas by your body, mind and money.

(2) You must not absent yourself from the meetings of the Sangh.

(3) You must without fear or favour expose any fault you may notice in the conduct of a Sakya.

(4) You must not be angry if you are accused of an offence but confess if you are guilty or state if you are innocent.

Proceeding, the Purohit said, “I shall next tell you what will disqualify you for membership of the Sangh. 24

(1) You cannot remain a member of the Sangh if you commit rape.

(2) You cannot remain a member of the Sangh if you commit murder.

(3) You cannot remain a member of the Sangh if you commit theft.

(4) You cannot remain a member of the Sangh if you are guilty of giving false evidence.

Sukiti bow his head in reverence said, “l am grateful to you sir, for telling me the rules of discipline of the Sakya Sangh. I assure you; I will do my best to follow them in letter and in spirit.”

14.CONFLICT WITH THE SANGH

Eight years had passed by since Sukiti was made a member of the Sakya Sangh. He was a very devoted and steadfast member of the Sangh. He took the same interest in the affairs of the Sangh as he did in his own. His conduct as a member of the Sangh was exemplary and he had endeared himself to all. In the eighth year of his membership, an event occurred which resulted in a tragedy for the family of Suddhodana and a crisis in the life of Sukiti. This is the origin of the tragedy-

Bordering on the State of the Sakyas was the State of the Koliyas. The two kingdoms were divided by the river Rohini. The waters of the Rohini were used by both the Sakyas and the Koliyas for irrigating their fields. Every season there used to be disputes between them as to who should take the water of the Rohini first and how much. These disputes resulted in quarrels and sometimes in fights. In the year when Sukiti was twenty-eight, there was a major clash over the waters between the servants of the Sakyas and the servants of the Koliyas, both sides suffered injuries. Coming to know of this, the Sakyas and the Koliyas felt that the issue must be settled once for all by war. The Senapati of the Sakyas, therefore, called a session of the Sakya Sangh to consider the question of declaring war on the Koliyas. Addressing the members of the Sangh, the Senapati said, “Our people have been attacked by the 25

Koliyas and they had to retreat. Such acts of aggression by the Koliyas have taken place more than once. We have tolerated them so far. But this cannot go on. It must be stopped and the only way to stop it is to declare war against the Koliyas. I propose that the Sangh do declare war on the Koliyas. Those who wish to oppose may speak.” Sukiti (later Sukiti) Gotama rose in his seat and said, “I oppose this resolution. War does not solve any question. Waging war will not serve our purpose. It will sow the seeds of another war. I feel that the Sangh should not be in haste to declare war on the Koliyas. A careful investigation should be made to ascertain who is the guilty party. I hear that our men have also been aggressors. If this be true, then it is obvious that we too are not free from blame.” The Senapati replied, “Yes, our men were the aggressors. But it must not be forgotten that it was our turn to take the water first.” Sukiti Gotama said, “This shows that we are not completely free from blame. I therefore propose that we elect two men from us and the Koliyas should be asked to elect two from them and the four should elect a fifth person and these should settle the dispute.” A duly amendment was moved by Sukiti Gotama. But the Senapati opposed the amendment, saying, “I am sure that this menace of the Koliyas will not end unless they are severely punished. The resolution and the amendment had therefore to be put to vote.” The amendment moved by Sukiti Gotama was put first. It was declared lost by an overwhelming majority. The Senapati next put his own resolution to vote. Sukiti Gotama again stood up to oppose it and said, “I beg the Sangh, not to accept the resolution. The Sakyas and the Koliyas are close relations. It is unwise that they should destroy each other.” The Senapati encountered the plea urged by Sukiti Gotama. He stressed that in war the Khattiyas cannot make a distinction between relations and strangers. They must fight even against brothers for the sake of their kingdom. We must fight to safeguard our property and subjects. Sukiti again raised objection and said, “Enmity will show the seed of another enmity. This must be first solved by dialogue.” A few members were agreed with Sukiti proposal. They 26

thought and agreed that war was not only solution. The Senapati, getting impatient, said, “It is unnecessary to enter upon this philosophical discussion. The point is that Sukiti is opposed to my resolution. Let us ascertain what the Sangh has to say about it by putting it to vote.” Accordingly, the Senapati put his resolution to vote. It was passed by an overwhelming majority. Sukiti still opposed. Raising voice against the majority was considered offence of sangha. Sangha further scheduled for meeting in next day for next course of action. Accordingly, the meeting was held next day. When the Sangh met, Senapati proposed that he be permitted to proclaim an order calling to arms for the war against the Koliyas. Every Sakya between the ages of 20 and 50. The meeting was attended by all members the Sangh had voted in favour of a declaration of war against the Koliyas. Unfortunately, those who were also not in favour of war, none of them had the courage to say so openly. Perhaps they knew the consequences of opposing the majority. Seeing that his supporters were silent, Sukiti stood up, and addressing the Sangh, said, “Friends, you may do what you like. You have a majority on your side, but I am sorry to say I shall oppose your decision in favour of war. I shall not join your army and I shall not take part in the war.” The Senapati, replying to Sukiti Gotama and said, “Do remember the vows you had taken when you were admitted to the membership of the Sangh. If you break any of them you will expose yourself to public shame.” Sukiti replied, “Yes, I have pledged myself to safeguard the best interests of the Sakyas by my body, mind and money. But I do not think that this war is in the best interests of the Sakyas. What is public shame to me before the best interests of the Sakyas? He proceeded to caution the Sangh by reminding it of how the Sakyas have become the vassals of the King of Kosala by reason of their quarrels with the Koliyas. It is not difficult to imagine that war will give him a greater handle to further reduce the freedom of the Sakyas.” The Senapati grew angry and addressing Sukiti, said, “Your eloquence will not help you. You must obey the majority decision of the Sangh. You are perhaps counting upon the fact that the 27

Sangh has no power to order an offender to be hanged or to exile him without the sanction of the king of the Kosalas and that the king of the Kosalas will not give permission if either of the two sentences was passed against you by the Sangh. But remember the Sangh has other ways of punishing you. For this the Sangh does not have to obtain the permission of the king of the Kosalas. These are-

- The Sangh can declare a social boycott against your family.

- The Sangh can confiscate your family lands.

Sukiti realised the consequences that would follow if he continued his opposition to the Sangh in its plan of war against the Koliyas. He had three alternatives to consider—

- To join the forces and participate in the war.

- To consent to being hanged or exiled.

- To allow the members of his family to be condemned a social boycott and confiscation of property.

He was firm in not accepting the first. As to the third he felt it was unthinkable. Under the circumstances, he felt that the second alternative was the best. Accordingly, Sukiti spoke to the Sangh, “Please, do not punish my family. Do not put them in distress by subjecting them to a social boycott. Do not make them destitute by confiscating their land which is their only means of livelihood. They are innocent. I am the guilty person. Let me alone suffer for my wrong. Sentence me to death or exile, whichever you like. I will willingly accept it and I promise I shall not appeal to the king of the Kosalas.”

The Senapati said, “It is difficult to accept your suggestion. For even if you voluntarily agreed to undergo the sentence of death or exile, the matter is sure to become known to the king of the Kosalas and he is sure to conclude that it is the Sangh which has inflicted this punishment and take action against the Sangh.” Sukiti said, “If this is the difficulty, I can easily suggest a way out. I can become a Parivajjaka and leave this country. It is a kind of an exile.” The Senapati thought this was a good solution. But he had still some doubt about Sukiti being able to give effect to it. 28

So, the Senapati asked Sukiti, “How can you become a Parivajjaka unless you obtain the consent of your parents and your wife?” Sukiti assured him that he would do his best to obtain their permission. He said, “I promise to leave this country immediately whether I obtain their consent or not.” The Sangh felt that the proposal made by Sukiti was the best way out and they agreed to it. Meeting was just about conclude and the Sangh was about to rise when a young Sakya got up in his place and said, “Give me a hearing, I have something important to say.” Being granted permission to speak, he said, “I have no doubt that Sukiti Gotama will keep his promise and leave the country immediately. There is, however, one question over which I do not feel very happy. Now that Sukiti will soon be out of sight, does the Sangh propose to give immediate effect to its declaration of war against the Koliyas? I want the Sangh to give further consideration to this question. In any event, the king of the Kosalas is bound to come to know of the exile of Sukiti Gotama. If the Sakyas declare a war against the Koliyas immediately, the king of Kosalas will understand that Sukiti left only because he was opposed to war against the Koliyas. This will not go well with us. I, therefore, propose that we should also allow an interval to pass between the exile of Sukiti Gotama and the actual commencement of hostilities so as not to allow the King of Kosala to establish any connection between the two.” The Sangh realised that this was a very important proposal. And as a matter of expediency, the Sangh agreed to accept it. Thus ended the tragic session of the Sakya Sangh.

15.PARTING WORDS

The news of decision made by the Sakya Sangh had travelled to the Suddhodana at palace long before the return of Sukiti Gotama. On reaching home, he found his parents weeping and plunged in great grief. Suddhodana said, “We were talking about the evils of war. But I never thought that you would go to such lengths.” Sukiti replied, “I too did not think that things would take such a turn. I was hoping that I would be able to win over the Sakyas to the cause of peace 29

by my argument. Unfortunately, our military officers had so worked up the feelings of the men that my argument failed to have any effect on them. But I hope you realise how I have saved the situation from becoming worse. I have not given up the cause of truth and justice and whatever the punishment for my standing for truth and justice, I have succeeded in making its infliction personal to me.” Suddhodana was not satisfied at the reply of prince and said, “You have not considered what is to happen to us.” “But that is the reason why I undertook to become a Parivajjak. Consider the consequences if the Sakyas had ordered the confiscation of your lands,” replied Sukiti. Suddhodana cried, “But without you what is the use of these lands to us? Why should not the whole family leave the country of the Sakyas and go into exile along with you?” Prajapati Gotami, who was weeping, joined Suddhodana in argument, saying; “I agree with your father’s opinion. How can you go alone leaving us here like this?” Sukiti said, “Mother, have you not always claimed to be the mother of a Khattiya? Is that not so? You must then be brave. This grief is unbecoming of you. What would you have done if I had gone to the battlefield and died? Would you have grieved like this?”. Gotami continued, “No, that would have been befitting a Khattiya. But you are now going into the jungle far away from people, living in the company of wild beasts. How can we stay here in peace?” He asked to Gotami, “You say, I should take along you with me. How can I take you all with me? Nanda is only a child. Rahul my son is just born. Can you come leaving them here?” Gotami was not satisfied. She urged, if, it was possible for all of them to leave the country of the Sakyas and go to the country of the Kosalas under the protection of their king. To this, Sukiti said, “But mother! What would the Sakyas say? Would they not regard it as treason? Besides, I pledged that I will do nothing either by word or by deed to let the king of the Kosalas know the true cause of my Parivajja. “It is true that I may have to live alone in the jungle. But which is better? To live in the jungle or to be a party to the killing of the Koliyas”. Father Suddhodhana said, “Why do you not postpone the idea of 30

Parivajja. It could be possible that Sangha reconsidered this matter and allow you to stay here.” This idea was extremely opposed by Sukiti and said, “It is because I promised to take Parivajja that the Sangh decided to postpone the commencement of war against the Koliyas. “It is possible that after I take Parivajja, the Sangh may be persuaded to withdraw their declaration of war. All this depends upon my first taking Parivajja. I have made a promise and I must carry it out. The consequences of any breach of promise may be very grave both to us and to the cause of peace. Mother, do not now stand in my way. Give me your permission and your blessings.” Gotami and Suddhodana kept silent. Then Sukiti went to the apartment of Yasodhara. Seeing her, he stood silent, not knowing what to say and how to say it. She broke the silence by saying, “I have heard all that has happened at the meeting of the Sangh at Kapilavatthu.” He asked her, “Yasodhara, tell me what you think of my decision to take Parivajja?” He expected that she would collapse. Nothing of the kind happened. With full control over her emotions, she replied, “What else could I have done if I were in your position? I certainly would not have been a party to a war on the Koliyas. Your decision is the right decision. You have my consent and my support. I too would have taken Parivajja along with you. If I do not, it is only because I have Rahula to look after. I wish, it had not come to this. But we must be bold and brave and face the situation. Do not be anxious about your parents and your son. I will look after them till there is life in me. All I wish is that now that you are becoming a Parivakjaka, leaving behind all who are near and dear to you, you will find a new way of life which would result in the happiness of mankind.” Sukiti Gotama was greatly impressed. He realised as never before what a brave, courageous and noble-minded woman Yasodhara was, and how fortunate he was in having her as his wife and how fate had put them asunder. He asked her to bring Rahula. He cast his fatherly look on him and left. Leaving his home. Sukiti thought of taking Parivajja at the hands of Bharadaja who had his Aram at Kapilavatthu. Accordingly, he rose the next day and started his journey for 31

the Aram on his favourite horse Kanthaka with his servant Channa walking along. As he came near the Aram, men and women came out and thronged the gates to meet him. And when they came up to him, their eyes wide open in wonder, they performed their due homage with hands folded like a lotus calyx. Then they stood surrounding him, their minds overpowered by passion, as if they were drinking him in with their eyes motionless and blossoming wide with love. Thus, the women only looked upon him, simply gazing with their eyes. They spoke not, nor did they smile. Sukiti did not like Suddhodana and Prajapati Gotami to be present to witness his Parivajja. For he knew that they would break down under the weight of grief. But they had already reached the Aram without letting him know. As he entered the compound of the Aram, he saw in the crowd his father and mother. Seeing his parents, he first went to them and asked for their blessing. They were so choked with emotion that they could hardly say a word. They wept and wept, held him fast and soaked him with their tears. Channa had tied Kanthaka to a tree in the Aram and was standing. Seeing Suddhodana and Prajapati in tears he too was overcome with emotion and was weeping. Separating himself with great difficulty from his parents, Sukiti went to the place where Channa was standing. He gave him his dress and his ornaments to take back home. Then he had his head shaved, as was required for a Parivajjaka. His cousin Mahanama had brought the clothes appropriate for a Parivajjaka and a begging bowl. Sukiti wore them. Having thus prepared himself to enter the life of a Parivajjaka, Sukiti approached Bharadaja to confer on him Parivajja. Bharadwaja with the help of his disciples performed the necessary ceremonies and declared Sukiti Gotama to have become a Parivajjaka. Remembering that he had given a double pledge to the Sakya Sangh to take Parivajja and to leave the Sakya kingdom without undue delay, Sukiti Gotama immediately on the completion of the Parivajja ceremony started on his journey. The crowd which had gathered in the Aram was unusually large. That was because the circumstances leading to Gotama’s Parivajja 32

were so extraordinary. As the prince stepped out of the Aram the crowd also followed him. He left Kapilavatsu and proceeded in the direction of the river Anoma. Looking back, he saw the crowd still following him. He stopped and addressed them, saying, “Brothers and sisters, there is no use following me. I have failed to settle the dispute between the Sakyas and the Koliyas. But if you create public opinion in favour of settlement you might succeed. Therefore, be so good as to return.” Hearing his appeal, the crowd started going back. Suddhodana and Gotami also returned to the palace. Gotami was unable to bear the sight of the robes and the ornaments discarded by Sukiti. She had them thrown into a lotus pool. Sukiti Gotama was only twenty-nine when he underwent Parivajja. This was an act of supreme sacrifice willingly made by him. It was a brave and a courageous act. There is no parallel to it in the history of the world. How true were the words of Kisa Gotami, a Sakya maiden referring to Sukiti Gotama, she said, “Blessed indeed is the mother, blessed indeed is the father, who has such a son. Blessed indeed is the wife who has such a husband.”

16.THE PRINCE AND THE SERVANT

Channa the charioteer of prince was still following the prince. Sukiti said, “Channa, you too should have gone back home with Kanthaka.” But he refused to go. He insisted on. Seeing the Prince off with Kanthaka at least to the banks of the river Anoma and so insistent was Channa that the Gotama had to yield to his wishes. At last, they reached the banks of the river Anoma. Then turning to Channa, he said, “Good friend, your devotion to me has been proved by thus following me. I am wholly won in heart, ye who have such a love for your master. I am pleased with your noble feelings towards me, even though I am powerless of conferring any reward. Who would not be favourably disposed to one who stands to him as bringing him reward? But even one’s own people commonly become mere strangers in a reverse of fortune. A son is brought up for the sake of the family, the father is honoured by the son for the sake of his own future 33

support. The world shows kindness for the sake of hope. There is no such thing as unselfishness without a motive. You are the only exception. Take now this horse and return. The king, with his loving confidence, still unshaken, must be enjoined to stay his grief. Tell him, I have left him with no thirst for heaven, with no lack of love, nor feeling of anger. He should not think of mourning for me who am thus gone forth from my home. Union, however long it may last, in time it will come to an end. Since separation is certain, how shall there not be repeated severing from one’s kindred? At a man’s death there are doubtless heirs to his wealth but heirs to his merit are hard to find on the earth or exist not at all. The king, my father, requires to be looked after. The king may say, ‘He is gone at a wrong time.’ But there is no wrong time for duty. Do you address the king, 0 friend! with these and such like words; and do you use your efforts so that he may not even remember me? Do you repeat to my mother my utter unworthiness to deserve her affections? She is a noble person, too noble for words.” Having heard these words, Channa, overwhelmed with grief, made reply with folded hands in choked voice choked by emotion, “Seeing that you are causing affliction to your kindred, my mind, 0 my Lord, sinks down like an elephant in a river of mud. To whom would not such a determination as this of thine, cause tears, even if his heart were of iron. How much more if it were throbbing with love? Where is gone this delicacy of limb, fit to lie only in a palace, and where is the ground of the ascetic forest, covered with the shoots of rough Kusa grass? How could 0 Prince, by mine own will, knowing this your decision, carry back the horse to the sorrow of Kapilavatthu? Surely you will not abandon that fond old king your father, and second mother, worn with the care of bringing you up. You will not surely forget and abandon your wife endowed with all virtues, illustrious for her family, devoted to her husband and with a young son. You will not abandon the young son yours and of Yasodhara, worthy of all praise. Or even if your mind is resolved to abandon thy kindred and thy kingdom, thou will not, 0 Master, abandon me. I cannot go to the city leaving you behind in the forest. 34

What will the king say to me, returning to the city without you? What shall I say to your wife?” Having heard these words of Channa overcome with sorrow, Sukiti Gotama with the utmost gentleness answered, “Abandon this distress Channa, regarding thy separation from me. Even, if I through affection were not to abandon my kindred, death would still make us helplessly abandon one another. As birds go to their roosting-tree and then depart, so the meeting of beings inevitably ends in separation. As clouds, having come together, depart asunder again, such I consider the meeting and parting of living things. And since this world goes away, each one deceiving the other. It is not right to think anything thine own. Therefore, since it is so, grieve not, my good friend, but go. Say without reproaching me, to the people of Kapilavathhu. Let your love for him be given up, and hear his resolve.” Having heard this conversation between the master and the servant, Kanthaka, the noblest steed, licked his feet with his tongue and dropped hot tears. Gotama stroked him and addressed him like a friend, “Do not shed tears, Kanthaka. Bear with it, thy labours will soon have its fruit.” Then Gotama, having bidden good-bye to Kanthaka and Channa, went on his way. While his master, thus regardless of his kingdom, was going to the ascetic-wood in mean garments, the groom, tossing up his arms, wailed bitterly and fell on the ground. Having looked back again, he wept aloud, hopeless and repeatedly lamenting, started on his return journey. On the way, sometimes he pondered, sometimes he lamented, sometimes he stumbled and sometimes he fell, and so going along, wretched through his devoted attachment, he performed all kinds of actions on the road knowing not what he was doing.

17.THE RETURN OF CHANNA

Channa was in deep distress, when his master thus went into the forest. He made every effort on the road to dissolve his load of sorrow. His heart was so heavy that the road which he used to traverse in one night with Kanthaka, that same road he now took eight days to travel, pondering 35

over his lord’s absence. The horse Kanthaka, though he still went on bravely, fagged and had lost all spirit. He, in the absence of his master seemed to have lost all his beauty. And turning round towards the direction in which his master went, he neighed repeatedly with a mournful sound. Pressed with hunger, he welcomed not, nor tasted any grass or water on the road. Slowly the two at long last reached Kapilavatthu which seemed empty when deserted by Gotama. They reached the city in body but not in spirit. When the two, their brightness gone and their eyes dim with tears, slowly entered the city, it seemed all bathed in gloom. Having heard that they had returned with their limbs all relaxed, coming back without the pride of the Sakya race, the men of the city shed tears. Full of wrath, the people followed Channa in the road, crying behind him with tears, “Where is the king’s son, the glory of his race and his kingdom? The city without him has no charms for us. Next, the women crowded to the rows of windows, crying to one another. Having seen that his horse had an empty back, they closed the windows again and wailed aloud.

18.THE FAMILY IN MOURNING

The members of the family of Suddhodana were anxiously awaiting the return of Channa in the hope that he might persuade Gotama to return home. There, they saw Kanthaka without the prince. Gotami, abandoning all self-control, cried aloud, “With his long arms and lion gait, his bull like eyes, and his beauty, bright like gold, his broad chest, and his voice deep as a drum or a cloud, should such a hero dwell in a hermitage? This earth is indeed unworthy as regards that peerless doer of noble actions. For such a virtuous hero has gone away from us. Those two feet of his, tender with their beautiful web spread between the toes, with their ankles, concealed and soft like a blue lotus, how can they, bearing a wheel mark in the middle, walk on the hard ground of the skirts of the forest? That body, which deserves to sit or lie on the roof of a palace, honoured with costly garments, aloes, and sandalwood, how will that manly body live in the woods, exposed to the attacks of the cold, 36

the heat, and the rain? “He who was proud of his family, goodness, strength, energy, sacred learning, beauty, and youth, who was ever ready to give, not ask, how will he go about begging alms from others? He who, lying on a spotless golden bed, was awakened during the night by the concert of musical instruments, how alas! will he, my ascetic, sleep today on the bare ground with only one rag of cloth?” having said, she fainted. Having heard this piteous lamentation, the women, embracing one another with their arms, rained tears from their eyes. Then Yasodhara, forgetting that she had permitted him to go, also fell upon the ground in utter bewilderment. Alas! the mind of that wise hero is terribly stern, gentle as his beauty seems. It is pitilessly cruel. Who can desert of his own accord such an infant son with his inarticulate talk, one who would charm even an enemy? But what can I do? My grief is too heavy for me to bear.” Yasodhara wept and wept aloud though she was self-possessed by nature, yet in her distress she had lost her fortitude. Seeing Yasodhara thus bewildered with her wild utterances of grief and fallen on the ground, all the women cried out, with their faces streaming with tears like large lotuses beaten by the rain. Having heard of the arrival of both Channa and Kanthaka, and having learned of the fixed resolve of his son, Suddhodana fell struck down by sorrow. Distracted by his grief for his son, being held up for a moment by his attendants, Suddhodana gazed on the horse with his eyes filled with tears, and then falling on the ground wailed aloud. 37

PART II

RENUNCIATION FOR EVER

- From Kapilavatthu to Rajagaha

- King Bimbisara and His Advice

- Gotama answers Bimbisara

- News of Peace

- The Problem in a New Perspective

38

1.FROM KAPILAVATTHU TO RAJAGAHA

Sukiti with determined thought, he crossed the Ganges, fearing not her rapid flow. On his way, he halted at the hermitage of Saki (might have donated by her), then at the hermitage of another name Padma (Donated by her) and then at the hermitage of the sage Rivata. All of them entertained him. Having seen his personality and dignity and his splendid beauty, surpassing all other men, the people of that region were all astonished at him wearing the clothes of a parivajjaka. On seeing him, he who was going elsewhere stood still, and he who was standing there followed him on the way. He who was walking gently and gravely ran quickly, and he who was sitting at once sprang up. Some people reverenced him with their hands, others in worship saluted him with their heads. Some addressed him with affectionate words; not one went on without paying him homage. Those who were wearing gay-coloured dresses were ashamed when they saw him. Those who were talking on random subjects fell to silence; no one indulged in an improper thought. His eyebrows, his forehead, his mouth, his body, his hand, his feet, or his gait, whatever part of him anyone beheld, that at once rivetted his gaze. After a long and arduous journey Gotama reached to Rajagaha. It was surrounded by five hills and was well guarded and adorned with mountains. It was supported and hallowed by auspicious and sacred places. He selected a spot at the foot. There was a small hut made of the leaves of trees for his sojourn. Kapilavatthu by foot is nearly 400 miles distant from Rajagaha. This long journey Sukiti Gotama did all on foot.

2.KING BIMBISARA AND HIS ADVICE

Next day, in Rajagaha, Sukiti got up early in the morning and started to go into the city with a begging bowl asking for alms. A vast crowd gathered round him. Then Seniya Bimbisara, the lord of the kingdom of the Magadhas, saw from the outside of his palace the immense concourse of people, and asked the reason of it. A courtier recount it to him, “He is the son of the king of the Sakyas, who is now an ascetic. It is he at whom the people are gazing at. He has 39

forsaken his kingdom to avoid conflict between his people. Some people say, ‘he will become enlightened one’”. The king, having heard this and perceiving its meaning in his mind, thus at once spoke to that courtier, “Let it be known where he is going”. The courtier, receiving the command, followed the prince. With fixed eyes, seeing only a yoke’s length before him, with his voice hushed, and his walk slow and measured. He, the noblest of mendicants, went begging for alms, keeping his limbs and his wandering thoughts under control. Having received such alms as were offered, he retired to a lonely corner of the mountain; and having eaten it there, he ascended the hut. In that wood, thickly filled with lodhra trees, having its thickness resonant with the notes of the peacocks, he, the sun of mankind, shone, wearing his red dress, like the morning sun above the eastern mountains. That royal courtier having thus watched him there, related it all to the king. The king when he heard it, in his deep veneration, started himself to go there with a modest retinue. Like a mountain in stature, the king ascended the hill. There he beheld Gotama, resplendent as he sat on his hams, with subdued senses, as if the mountain was moving, and he himself was a peak thereof. Him, distinguished by his beauty of form and perfect tranquillity, filled with astonishment and affectionate regard, the king of men approached. Bimbisara having courteously drawn near to him, inquired of his well beings. Gotama with equal gentleness assured the king of his health of mind and freedom from all ailments. Then the king sat down on the clean surface of the rock, and being seated, he thus spoke, desiring to convey his state of mind, “I have a strong friendship with your family, come down by inheritance and well proved; since from this, a desire to speak to thee, my son, has arisen in me, therefore, listen to my words of affection. When I consider thy race, thy fresh youth, and thy conspicuous beauty, I wonder whence comes this resolve of thine, so out of all harmony with the rest, set wholly on a mendicant’s life, not on a kingdom? Thy limbs are worthy of red sandalwood perfumes. They do not deserve the rough contact of pebbles, dust and rocks; this hand of thine is fit to 40

protect subjects, it deserves not to hold food given by another. If, therefore, gentle youth, thou desire not thy paternal kingdom, then in thy generosity, accept forthwith one half of my kingdom. If thou act thus, there will be no sorrow caused to thine own people, and by the mere lapse of time imperial power at last flies for refuge to the tranquil mind, therefore, be pleased to do me this kindness. The prosperity of the good becomes very powerful, when aided by the good. But if from thy pride of race, thou dost not now feel confidence in me, then plunge with thy arrows into countless armies, and with me as thy ally seek to conquer thy foes. Choose thou, therefore, one of these ends. Wealth, and pleasure pursue love and the rest, in reverse order. These are the three objects in life; when men die, they pass into dissolution as far as regards this world. Therefore, by pursuing the three objects of life, cause this personality of thine to bear its fruit. Many old people say that when the attainment of religion, wealth and pleasure is complete in all its parts, then the end of man is complete. Do not thou let these two brawny arms lie useless which are worthy to draw the bow. They are well fitted to conquer the three worlds, much more the earth. I speak this to you out of affection, not through love of dominion or through arrogance beholding this mendicant-dress of thine, I am filled with compassion and I shed tears. O, thou who desirest the mendicant’s stage of life, enjoy pleasures now, in due time ere old age comes on and overcomes this thy beauty, well worthy of thy illustrious race. The old man can obtain merit by religion old age is helpless, for the enjoyment of pleasures; therefore, they say that pleasures belong to the young man, wealth to the middle-aged, and religion to the old. Youth in this present world is the enemy of religion and wealth—since pleasures, however much we guard against them, are hard to hold, therefore, wherever pleasures are to be found, there thy youth seize them. Old age is prone to reflection, it is grave and intent on remaining quiet; it attains un-impassionedness with but little effort, unavoidably, and for very shame. Therefore, having passed through the deceptive period of youth, fickle, intent on external objects, 41

heedless, impatient, not looking at the distance, they take breath like men who have escaped safe through a forest. Let, therefore, this fickle time of youth first pass by, reckless and giddy, our early years are earmarked for pleasure, they cannot be kept from the power of the senses.

3.GOTAMA ANSWERS BIMBISARA

The monarch of the Magadhas, Bimbisara thus well spoke well and strong, but having heard it, the prince did not falter. He was firm like a mountain. Being thus addressed by the monarch of the Magadhas, Gotama, in a strong speech with friendly face, self-possessed, unchanged, thus made answer. “What you have said is not to be called a strange thing for thee. 0 King! born as thou art in the great family whose ensign is the lion, and lover as thou art of thy friends, that ye should adopt this line of approach towards him who stands as one of thy friends is only natural. Amongst the evil-minded, a friendship worthy of their family, ceases to continue and fades; it is only the good who keep increasing the old friendship of their ancestors by a new succession of friendly acts. But those men who act unchangingly towards their friends in reverses of fortune, I esteem in my heart as true friends. Who is not the friend of the prosperous man, in his times of abundance? So those who, having obtained riches in the world, employ them for the sake of their friends and religions, their wealth has real solidity, and when it perishes it produces no pain at the end. This thy suggestion concerning me, 0 King, is prompted by pure generosity and friendship; I will meet thee courteously with simple friendship, I would not utter aught else in my reply. I am not so afraid even of serpents, nor of thunderbolts falling from heaven, nor of flames blown together by the wind, as I am afraid of these worldly objects. These transient pleasures, the robbers of our happiness and our wealth, and which float empty and like illusions through the world, infatuate man’s minds even when they are only hoped for. The victims of pleasure attain not to happiness even in the heaven of the gods, still less in the world of mortals; he who is athirst is never satisfied with pleasures, as the fire, the friend of the 42

wind, with fuel. There is no calamity in the world like pleasures, people are devoted to them through delusion. When he once knows the truth and so fears evil, what wise man would of his own choice desire evil? When they have obtained all the earth girdled by the sea, kings wish to conquer the other side of the great ocean; mankind is never satiated with pleasures, as the ocean with the waters that fall into it. When it had rained a golden shower from heaven, and when he had conquered the continents and had even obtained the half of worldly objects. Success in pleasure is to be considered a misery in the man of pleasure, for he becomes intoxicated when the pleasures of his desire are attained; through intoxication he does what should not be done, not what should be done; and being wounded thereby he falls into a miserable end. These pleasures which are gained and kept by toil, which after deceiving leave you and return whence, they came. These pleasures which are but borrowed for a time. What man of self-control, if he is wise, would delight in them? What man of self-control could find satisfaction in these pleasures which are like a torch of hay, which excite thirst when you seek them and when you grasp them? What man of self-control could find satisfaction in these pleasures which are like flesh that has been, flung away, and which produces misery by their being held in common with kings? What man of self-control could find satisfaction in these pleasures, which, like the senses, are destructive, which bring calamity on every hand to those who abide in them? Those men of self-control who are bitten by them in their hearts, fall into ruin and attain not bliss. What man of self-control could find satisfaction in these pleasures, which are like an angry, cruel serpent? Even if they enjoy them men are not satisfied like dogs famishing with hunger over a bone what man of self-control could find satisfaction in these pleasures, which are like a skeleton composed of dry bones? He whose intellect is blinded with pleasures, the wretch, who is the miserable slave of hope for the sake of pleasures, well deserves the pain of death even in the world of living. Insects for the sake of the brightness fly into the fire, the fish greedy for the flesh 43